Welcome to NewPages.com

NewPages is your best guide to literary magazines, indie publishing, creative writing programs, writing and literary events, writing contests, calls for submissions, and more.

New Calls for Submissions & Writing Contests

Check out the latest calls for submissions and writing contests from independent publishers, literary magazines, creative writing programs, and more.

The Goldilocks Zone 2022

Deadline: 2022-12-19

Aji Magazine is Accepting Submissions for the Spring 2023 Issue

Deadline: Rolling

Latest from the NewPages Blog

Enjoy new issues of literary magazines, new and forthcoming titles from indie and university presses, and other literary news.

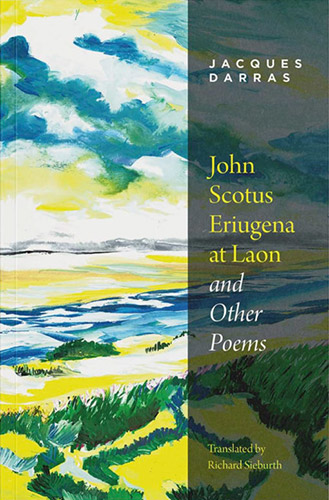

New Book :: John Scotus Eriugena at Laon

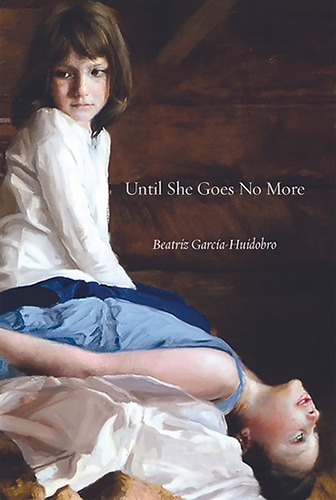

New Book :: Until She Goes No More

Discover More

NewPages Blog

Stay up-to-date with the latest literary news from magazines, indie and university presses, and more.

Submission Calls

See which magazines, anthologies, and presses are open to submissions.

Writing Contests

Dive into contests from literary magazines, indie publishers, writing programs, and more.

Young Writers Guide

Find a curated list of vetted, no-fee contests and publications that accept entries from young writers.

Writing Conferences

Discover upcoming writing conferences and literary events across the United States, Canada, and abroad.

Lit Mags

Explore a vetted list of hundreds of print, online, and digital literary magazines.

Alt Mags

Publications on topics including ecology, health, human rights, and more.

Mag Stand

A regularly updated list of the latest issues of literary and alternative magazines.

Independent Bookstores

Support new and used indie bookstores across the United States, its territories, and Canada.

Indie Presses

A leading resource for independent, university, and small presses.

Book Stand

Discover new and forthcoming titles from indie and university presses.

Creative Writing Programs

Your first stop for undergraduate programs, classes, and degrees as well as graduate creative writing programs offering MA, MFA, and PhD degrees.

Write for Us

NewPages is always looking for short reviews of books and magazines!

Book Reviews

Discover your next read with short reviews of new and forthcoming titles.

Mag Reviews

Enjoy short reviews of entire issues of literary magazines and shorter pieces.

Mailing Lists

NewPages offers mailings lists of independent bookstores in the US and Canada as well as public libraries and academic libraries in the US.

Advertise

Get more visibility for your journal, press, creative writing program, literary or writing event, call, or contest with an advertisement on NewPages.

Subscribe to our Email Newsletter

Subscribe to the NewPages Newsletter to get weekly updates on submission opportunities, many before they go live on our site, as well as the latest issues of literary and alternative magazines, new and forthcoming titles from university and indie presses, upcoming events, and more.